Debate on State Responses to Covid-19

Beyond Border Sovereignty: Comparing State and

Regional Responses to Covid-19 in Africa and Europe

22nd of December, 2021

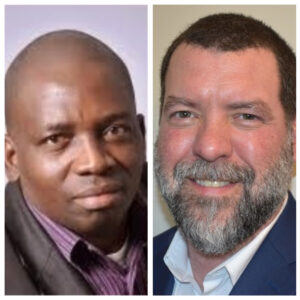

Samuel Ojo Oloruntoba and Cory Blad

Countries in Africa and Europe have adopted a mix of national and regional approaches to managing Covid-19 since its outbreak in 2019. The strategies in the two continents have produced different outcomes in terms of the rates of infections, recoveries, and fatalities. The effectiveness of national and regional institutions in Africa and Europe have affected the divergent outcomes. Regional economic institutions play a central organizational role in both cases, however massive differences in financial support mirror divergences. The need to further embed public health infrastructure in successful economic community cooperation is highlighted in both cases.

In the early months of the outbreak of the virus, Africa followed the examples of other regions and imposed national lockdowns in a bid to curb the spread of the virus. In this process, states commonly activated emergency laws, which restricted human rights and protection of the rule of law. More productive with regards to socio-economic stability, a regional approach has been adopted in fighting the Covid-19 pandemic, which has largely helped to mitigate its effects. Under the auspices of the African Union, the Africa Centres for Disease Control has taken the lead in responding to the pandemic on the continent. In West Africa, the Economic Community of West African States has supported member states with funding to purchase test kits, while the West Africa Health Organisation provides daily reports on infections, recoveries, and deaths. Differences in the capacity of African states to address the pandemic and its economic implications could pose long-term challenges in containing the spread of the virus as well as ensuring economic recovery. The porous borders between many countries in Africa present additional challenges and opportunities for a regional-based approach to pandemic response.

In Europe, national lockdowns were imposed. Unlike in Africa where a regional approach was immediately activated, bickering among members of the European Union resulted in delays before a regional approach could be activated. Institutional infrastructure advantages were initially ignored as national restrictions on travel, trade, and exports restricted regional public health coordination. Eventually, several regional economic recovery and public health funding initiatives (CRII and SURE, to name a few) were implemented to provide support for national member states. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control plays a complementary role by supporting the state to provide technical advice, information, and training, but national-level autonomy ensures this advisory capacity. This is like the role played by the Africa Centre for Disease Prevention and Control in terms of information dissemination and some supply coordination, but not with regards to research and development.

As the virus continues to evolve, we see how institutions remain critical to managing the pandemic. In Africa, where many years of neglect led to weak health infrastructures, regional institutions play important roles in mobilizing resources, training, and information distribution. The commitment of each respective Centre for Disease Prevention and Control in coordinating national health institutions needs to be reinforced, but the common experiential need to utilize economic community infrastructure in order to facilitate regional cooperation highlights the long-term impact of social disembeddedness. Both in Africa and Europe, it is imperative build stronger national and regional health infrastructure to combat future pandemics.

Samuel Ojo Oloruntoba

Samuel Ojo Oloruntoba is an Adjunct Research Professor at the Institute of African Studies, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada and Honorary Professor at the Thabo Mbeki School of Public and International Affairs, University of South Africa. He is also a Faculty Associate at the African School of Governance and Policy Studies.

Cory Blad

Cory Blad, Ph.D. is interim Dean of the School of Liberal Arts and Professor of Sociology at Manhattan College. His work examines political legitimation in the context of neoliberal capitalism.

Read the other essays on State Responses to Covid-19 here: