Debate on The Contested Provisioning of Care and Housing

Bringing life’s work to market: Performation struggles and incomplete commodification on the margins

15th of September, 2022

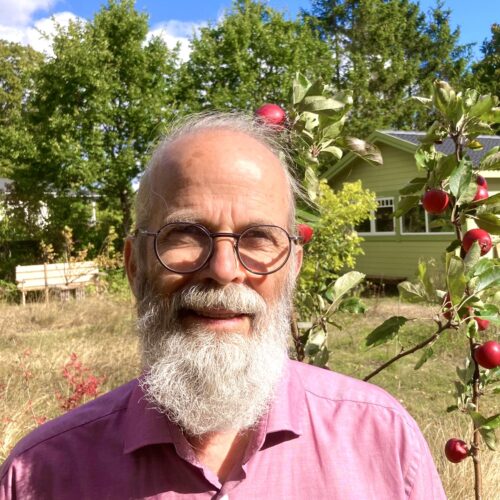

Christian Berndt

“Housing markets are less liquid, but people are very careful when they buy houses. It’s typically the biggest investment they’re going to make, so they look around very carefully and they compare prices. The bidding process is very detailed.“

This is how the economist Eugene Fama responded to a question about the efficiency of the real estate and housing market in an interview on the eve of the 2008/2009 US mortgage crisis (Clement 2007). Fama is considered the “father” of the so-called efficient market hypothesis. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2013 for his research. Even in the face of emerging distortions, Fama saw no reason to abandon the efficiency assumption. For him, house and apartment buyers in particular weigh their decisions carefully. They look around carefully and compare prices, the material condition of the properties and their locations. In short, they calculate rationally. This is precisely how perfect market competition works in mainstream economics. In their simplest form, markets are efficient because market prices reflect all available information. For neoclassical economists, markets are infallible and are therefore fundamentally better suited to solving environmental and social problems than, for example, the state or a social community.

A cascading number of crises that seem to follow each other in ever shorter time intervals have since made it increasingly difficult to dismiss suggestions of market failure in such a cavalier way. The ongoing presence of orthodox economic thinking notwithstanding, there is reason to believe that the times of radical market thinking and unfettered neoliberal marketization are finally over. This is a perfect moment to think differently about markets and marketization and to break to spell of the neoclassical market. I will use the space of this blog entry to do so on the example of housing, combining insights of “social studies of economization” (Çalışkan and Callon, 2010) and “geographies of marketization” (Berndt and Boeckler 2012, 2020) with Polanyian political economy. I will do so by making three related arguments:

The first is the conviction that it is marketization as a process that matters, and not markets as self-contained entities. The focus is on markets “in the making”, a process that is necessarily incomplete and unstable. As such marketization is the work of a large number of actors, human and non-human, who arrange markets in a delicate double play of entanglement and disentanglement – or, to use the words of STS scholars, “framing”. In the housing market framing is the work of a human-nonhuman working group of real estate agents who apply models and knowledge from their various practice disciplines; material devices such as valuation models and formulas, benchmarks, online platforms, maps, redlining; and of course wider regulatory structures. What would the marketization of housing be without institutionalized property rights, legal norms or various kinds of standards? But assembling these heterogeneous agents is not enough. Before they can be entangled other connections have to be cut. When real estate practitioners perform their calculations they have to bracket out all kinds of “non-economic” considerations. All these provide the frames that make market transactions possible. But framing is never complete. The “entities” in question exceed the various frames, there are “overflows” that cause friction and irritation. In the case of housing this may concern non-market valuations of a certain neighborhood or emotional attachment to the places in question. Or protests against the growing presence of various “others” (wealthy gentrifiers, people perceived as “foreign”).

Second, by reading marketization from below, that is, from the vantage point of actually-existing market settings, prescriptive orthodox representations lose their overshadowing hegemony. There are always additional logics and rationalities at work. The ideal-type understanding of the market is always only one of these logics. This may happen in relative harmony, but more often involves struggles between antagonistic rationalities, strategies, and values. With Karl Polanyi (1957) one might point to his well-known institutional forms, each associated with a particular social pattern: in addition to price-making housing markets there are collective, cooperative housing projects that are stabilized by symmetrical ties of community; or state-administered social housing, working along redistributive logics. But what is crucial is that neither of these logics exist in isolation. A cooperative housing project, for instance, can never fully disentangle itself from the redistributive state (taxes, property title) or from market forces (land prices, wider rent levels). There are potentially unlimited possibilities, giving form to institutionally diverse markets that can only adequately be mapped with careful empirical analysis: Markets are institutionally diverse and have to be studied in their diversity.

Third, when we start with the insight that marketization can never be fully successful because nothing can be commodified “all the way down” (Fraser, 2014), there is greater acknowledgement of how misfires and overflows set limits and provide openings for resistance and alternatives. There are obvious connections with Polanyi’s forceful argument that the expansion of “market organization in respect to genuine commodities was accompanied by its restriction in respect to fictitious ones” (1957, p. 79). For Polanyi the market was checked on the terrain of labor, land and money. As elements not originally produced for sale these are responsible for what he famously referred to as “double movement”.

Housing is a key terrain on which to study the ongoing unequal marketization and reframing of activities that have hitherto been relatively shielded from market logics. The agents involved are engaged in struggles over social reproduction. There are attempts to reclaim lost terrain in the name of state redistribution; for instance, when citizens voted for the re-municipalization of Berlin’s public housing stock after the city government sold it to private real estate companies; or when there are attempts to reclaim lost terrain in the name of communal sharing. In Zürich where about a quarter of rental housing is provided by Wohnungsbaugenossenschaften, voters have obliged the city government to increase this share to 30 percent. This reminds us that marketization always emerges as the effect of political struggles that inscribe new social differences onto existing ones, throwing into sharp relief that marketization is gendered, racialized, and immersed in class relations and that there is a need to center categories of difference in processes of marketization.

Such an understanding of markets as continuously in the making (marketization), as being institutionally variegated (diverse markets), and as involving incomplete commodification processes that are shot through with inequalities and power asymmetries (market struggles) can be considered as an emerging consensus within critical market studies. The “Contested Provisioning of Care and Housing” Workshop provided perfect examples for this, offering valuable state-of-the-art studies that illustrate perfectly what theoretically informed empirical analyses of marketization processes are capable of achieving.

References

Berndt, C., & Boeckler, M. (2012). Geographies of marketization. In T. Barnes, J. Peck, & E. Sheppard (Eds.), The New Companion to Economic Geography (pp. 199–212). Wiley-Blackwell.

Berndt, C., & Boeckler, M. (2020). Geographies of marketization: Performation struggles, incomplete commodification and the “problem of labour.” In C. Berndt, J. Peck, & N. Rantisi (Eds.), Market/Place: Exploring Spaces of Exchange (pp. 69–88). Agenda Publishing.

Çalışkan, K., & Callon, M. (2010). Economization, part 2: A research programme for the study of markets. Economy and Society, 39(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140903424519

Clement, D. (2007). Interview with Eugene Fama. The Region, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. https://www.minneapolisfed.org:443/article/2007/interview-with-eugene-fama (last accessed 3 October 2022)

Fraser, N. (2014). Can society be commodities all the way down? Post-Polanyian reflections on capitalist crisis. Economy and Society, 43(4), 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2014.898822

Polanyi, K. (1957). The economy as instituted process. In K. Polanyi, C. M. M. Ahrensberg, & H. W. W. Pearson (Eds.), Trade and Markets in the Early Empires (pp. 243–270). Free Press.

Christian Berndt

Christian Berndt is Professor of Economic Geography at the University of Zürich.

Read the other essays on the Contested Provisioning of Care and Housing here: