Debate on Deglobalization

Return to a societally steered market economy -

with new ecological and social development directions

25th of May, 2020

Dr. Rainer Land

1) Overcoming the global crises – human-made climate change, environmental and social crises, poverty, underdevelopment and inequality – requires a different kind of globalisation. Economic development would have to be geared globally to substantive goals, not to financial market gains.

There were societally steered market economies with development goals defined in terms of content: USA 1938 to 1968, Western Europe until 1968, Japan until 1989; today in China. An alternative globalization strategy must again be oriented to the model of a controlled market economy – with new and expanded goals. This does not require that the entire world community, currently comprising 193 states, agree on that but that the centres of economic development, China, the USA and the EU, must work together for mutual and shared benefit instead of fighting each other.

2) A controlled market economy is not a centrally administered economy; it presupposes goods and financial markets and independent enterprises (private and public, municipal, national and international), but steers innovation and investment in certain societally desired directions. It uses legal frameworks for this purpose and controls development using defined instruments: monetary and fiscal policy, credit management, exchange rate policy, innovation and industrial policy, science, wage policy, regional development, etc.

Guided economic development requires shared substantive goals, both nationally and globally. Ecological transformation and coping with climate change, social progress in the form of overcoming poverty, work with sufficient income, participation, health and social services, education – a better life for all. Decisions on economic development directions and the use of steering instruments must be based on these goals, which must be worked out in an open discourse, democratically decided and politically institutionalised. In a controlled market economy, framework conditions are designed in such a way that profits and returns on capital can only be achieved in accordance with such shared goals.

3) A comprehensive investment programme for a new globalisation strategy, oriented towards such goals, would be the starting point. A new, ecologically sound and societal progressive globalisation strategy requires an update of the regulatory system, an overcoming of the neo-liberal idea that economic development is determined by financial markets and shareholder value and cannot or must not be politically defined.

This requires a review of how historically successful steered market economies – the USA and Western Europe until 1973, Japan until 1989 and China today – have functioned or are functioning. Important points are: The regulation of financial markets and their subordination as serving the real economic development, controls on capital flow, regulation of exchange rates in a new international monetary system, participatory involvement of social groups (workers, environmental and consumer associations, regional actors) in long-term global investment programmes, public holdings in companies, management of ecological resources to ensure their conservation, use and reproduction, instruments of credit control, promotion of regional economic cycles and coordination with global cycles, regulation of the relationship between productivity and wage development.

4) Any economy that wants to steer economic development first needs a national steering system. This also applies to cooperative networks of economies that regulate and steer certain areas jointly, such as the euro zone, NAFTA, APEC, Brics and others. Only if the national regulatory systems work, economies are multinational or global capable of cooperation at all.

It is not a question of globalization versus de-globalization, but of other, societal desired directions of development instead of the dominant selection by financial markets.

5) To achieve this, one must not eliminate capital, but break the power of finance capital and neoliberal ideology. In doing so, one must include as allies companies and investors who can and want to make money with progressive developments.

At present, the change in the global balance of power necessary for this is not foreseeable. The USA and the EU continue to pursue a neoliberal strategy. The best that can be done today is to support the new Chinese globalization strategy, One Belt, One Road (The New Silk Road), to promote projects for the mutual and shared benefit of all and to participate in an ecologically and societally progressive orientation of this globalization strategy – instead of standing beside it as sceptical observers or trying to stop it. We need closer cooperation with China, because this is currently the only successful societally steered market economy with the experience and means to manage economic development on a global scale.

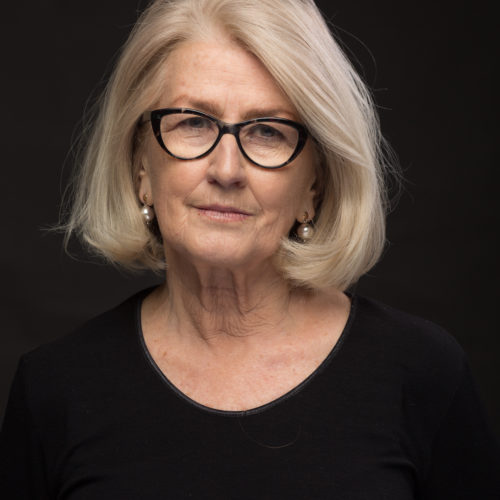

Rainer Land

Economist and Social Scientist

Thünen-Institute in Bollewick and Berlin

Germany

Read the other essays on Deglobalization here:

Anna Ząbkowicz, Maciej Kassner

Deglobalization and EU

Heiner Flassbeck

Neo-liberalism and Globalization

Alexandra Strickner

The neoliberal world market project has failed

Michele Cangiani

What kind of Deglobalization?

Andreas Novy

Globalization was Planned, Deglobalization was not.

Andreas Nölke

Deglobalization as a cornerstone of a new phase of organized capitalism

Judith Dellheim

Three Theses for our Debate on Deglobalization

Kurt Bayer

Does the Covid-19 crisis lead the EU towards Deglobalization?